Russia's pensions system: Economies of scale dominate

At a glance

• Consolidation has driven down pension fund numbers.

• The finance ministry and central bank have proposed a quasi-voluntary system to replace the second pillar.

• New investment assets proposed in favour of bank deposits.

• The first initial public offering of a pension fund financial group has made its debut on the Moscow Stock Exchange.

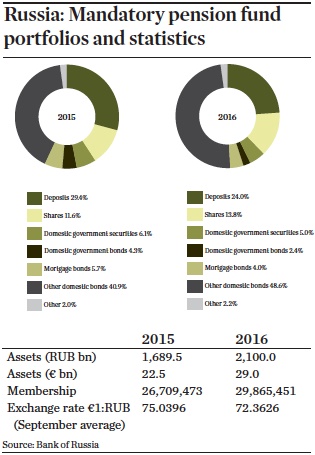

Russia’s mandatory non-state pension fund (NPF) assets grew by 18.6% year-on-year in rouble terms to RUB2,034bn (€29.6bn), according to Central Bank of Russia (CBR) data for mid-2016. At the same time, the number of pension providers continued to shrink.

As of late November, there were 43 NPFs signed up to the guarantee scheme of the Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA), an ultimate condition of second-pillar provision. This meant that 10 firms had left the industry or folded into existing DIA signatories.

This reduction has been driven by consolidation, which accelerated in 2016. Seven financial groups now control 90% of assets, with several individual NPFs merging into single platforms, including Future Financial Group, Safmar (see panels) and Gazfond.

In 2015, Future Financial Group, which consolidates the pension fund assets of Boris Mint’s O1 Group, started mergering of two of its funds, NPF Blagosostoyanie and NPF Stalfond into Future NPF. This process was completed in 2016.

“Both funds focus on mandatory pension insurance, so the merger enabled us to get rid of redundant departments while sustaining best business practice in customer care and corporate governance,” says Nikolay Sidorov, CEO of Future NPF.

The merger pushed Future into third place for pension assets (RUB232.7bn) and second in terms of membership (3.72m) according to CBR’s mid-2016 data. Half of the remaining four funds – Our Future (formerly Russian Standard) and Uralsib – are set to be integrated by the end of 2016.

Consolidation is one way that individual NPFs can grow, given the continuing pressures on the whole pensions system. The federal budget remains in deficit, leading to a moratorium on contributions for 2017-19, following on from a policy of freezes since 2014.

Previously 6% of the 22% social tax went towards the mandatory funds, the remainder went to the Pension Fund of the Russian Federation (PFR). Such has been the squeeze on the state system that in 2016 pensioners did not get their regular indexed increase, and have had to make do with a one-off payment of RUB5,000 planned for January 2017.

Within the government there has been pressure to remove the privately run compulsory second pillar from the so-called ‘social bloc’. This opposition has come from the Ministry of Labour and Social Protection and deputy prime minister Olga Golodets.

In response, the Ministry of Finance and CBR have put together an alternative pensions proposal, described as a “modernisation”.

The Future Financial IPO makes history

In October 2016, Future Financial Group became the first Russian pensions management group to raise funds through an IPO on the Moscow Stock Exchange, bringing in RUB11.7bn (€1.7bn) through the sale of 9.8m shares, valuing the company at RUB58.5bn.

Marina Rudneva, CEO of the group, describes the decision as the result of the changing pensions landscape imposed by the Bank of Russia: incorporation as joint stock companies, membership of the Deposit Insurance Agency guarantee scheme, the tightening of risk-management and asset quality requirements, and the fund mergers that have followed.

Future Financial Group’s acquisitions have given it a client base of 4.5m, which Rudneva describes as a unique-cross

selling opportunity, with significant sales potential for corporate and individual pension programes.

“After following all the central bank’s requirements pension market has become much more transparent, so there was the only one step left: to go public,” she explains. “Of course it’s not easy to be the pioneer, but the results of IPO shows us the large amount of interest from investors. Investors see growth opportunities and potential in the pension market.

“We noted the high level from retail investors, who purchased nearly RUB3bn of our paper. Currently 20% of the group is in free float.”

One of the rationales of the plan, unveiled at September’s Moscow Financial Forum, was that the existing system fails to provide adequate pensions for the middle classes.

While the current 22% social tax is entirely employer funded, the new plan proposes rising contributions from employees incrementally. They start at nothing in the first year increasing to a maximum 6% of salary. These monies will be accumulated in newly created Individual Pension Capital (IPC) accounts. The new system would be mandatory, but allow for five-year contributions breaks, and use existing savings in the NPFs as the first contribution.

Evgeny Yakushev, executive director of NPF Safmar, says that given six years of frozen contributions, the finance ministry and CBR are looking at opportunities to provide new streams of income for the pensions industry.

The government’s co-authors are discussing their proposal with the pensions industry, social partners, and the relevant ministries, with CBR aiming to draft a law at the beginning of 2017.

One of the elements under discussion is how the tax deduction that would apply, either to personal payments or concurrent social tax contributions, the latter is opposed by the ‘social bloc’. Other issues include how to make it mandatory, and whether it should cover the self-employed.

Yakushev is sceptical. “We have had a difficult economic situation where incomes have decreased, so it’s very difficult to see how the system could cover a large part of the population,” he says.

An alternative has been proposed by the Non-State Pension Fund Association (ANPF) – a self-regulatory organisation in the Russian pensions market – that would maintain contributions, but at about 1% rather than the frozen 6%. Yakushev, a board member of the ANPF, adds: “After the economy recovers, we could rethink the second pillar.”

Another issue is that most second-pillar members have opted for NPFs rather than the fund run by state-owned Vnesheconombank (VEB). This figure now exceeds 30m, about half of the economically active population. As Sidorov points out: “They have consciously chosen second-pillar pension savings as a financial instrument. Changing the system after 13 years of operation means questioning the trust of those people.”

In a further sign of popularity, as of the beginning of November 2016, there were 5.7m new applications in the mandatory system compared with 3.7m in the same period of 2015. Yakushev expects that number to rise to 7m by the end of 2016, with about 70% involving workers moving from VEB-managed accounts to the private system, and the remainder transferring between NPFs.

Increasing investment income in the private system has accounted for the interest, with the funds generating an average year-to-date return of 9.5% as of mid-2016, compared to inflation of 6.7%. The main trend has been a continuing shift into corporate bonds, alongside the CBR reducing the maximum exposure to bank deposits. The limit was cut from 65% to 40% in 2016.

The CBR envisages further reductions, with its first deputy chairman recently stating that the level should fall to 5-10% in order to free up assets to invest in the capital markets.

One of the main changes to investment regulations occured in June 2016, this allowed NPFs to participate directly in privatisations. This enabled pension funds to buy into the following month’s 10.9% share offering in Alrosa, Russia’s biggest diamond mining company. “With Alrosa growing at 40% for the time being, it’s been a fantastic investment,” says Yakushev.

Various alternative assets have also been suggested by the regulator, including high-tech start-ups, investment into small and medium-sized companies, securitisations and infrastructure bonds. The last would offer improved returns than those generated by municipal and regional bonds. But, they would need a good credit rating and guarantees from the administrative authorities to make them viable investments.

At the same time, the Russian finance ministry has initiated a proposal whereby the funds, as of 2017, would have to generate “an economically viable rate of return”, at amortised rather than market value. The risk premiums would be priced into each deal with the CBR as the final arbiter. NPFs would have to compensate for any losses or profit reduction out of their own resources. While the idea is to stamp out abuses such as funds investing in beneficiaries, the pensions industry has warned of the risk of pushing them into low-yielding investments.

On the regulatory front, the CBR has introduced risk management procedures that include shifting the evaluation of each transaction from the asset management companies to the NPFs themselves. “As a part of this process, we expect stress testing to be introduced in 2017,” says Yakushev.

With the funds gaining in experience, the finance ministry has proposed that they can manage the pensions assets directly rather than having to use asset management companies.

A creation of consolidation: NPF Safmar

Consolidation is the main driver behind the falling number of Russia’s compulsory non-state pension fund providers (NPFs) as their owners achieve economies of scale through mergers.

In September 2016, the number fell further as Safmar Financial Group, formerly BIN Group, merged four of its five NPFs into a single entity, NPF Safmar. The group itself, which started its pension fund acquisitions in 2011, is one of Russia’s largest financial conglomerates, with interests spanning banking (BIN Bank and MDM Bank), the insurance group VSK, Europlan, the country’s second biggest auto leasing company (which went public on December 2015), as well as real estate assets.

The merger was cleared by the Federal Antimonopoly Service of the Russian Federation in May, and approved by Bank of Russia in August.

NPF Safmar is the renamed Raiffeisen NPF, which dates back to 1994, with Raiffeisenbank Russia becoming a shareholder 10 years later. The fund, according to Alexander Lorenz, chairman of the advisory council, and formerly member of Raiffeisen Pension Fund’s supervisory board, became Russia’s most prominent foreign-owned fund and the last standing when it was acquired by the BIN Group in October 2015.

“In teaming up with other pension funds, Safmar retained the best practices instilled by the Raiffeisen Group, and additionally integrated those from the other funds,” says Lorenz.

“The European Pension Fund, for example, was a leader in the mandatory pension insurance market,” he says.

“Regionfond had extensive experience with large industrial enterprises that introduced pension plans for their employees, while Education & Science developed pension plans for students, teachers, professors and university researchers. Finally, Safmar works with companies on corporate pension plans.”

According to Lorenz, the merger will not affect obligations: “Customer agreements stay in effect; the terms of the investment income calculation and distribution, payout of pensions and surrender amounts will also remain unchanged.”

The newly merged firm ranked, as of the end of June 2016, sixth in terms of assets and fifth in membership. As of the end of September 2016, it had assets of RUB183.4bn (€2.7bn) in the second pillar and RUB8.3bn in the third, and respective memberships of 2.34m and 75,000.

Corporate bonds accounted for 45%, of the pensions savings portfolio, followed by shares (17%), deposits and cash (12% apiece), and mortgage participation certificates (9%).

It will grow further in 2017 following a merger with Doverie, the remaining fund in the group. As of mid-2016, Doverie had assets of RUB67.3bn and membership exceeding 1.48m.

Prior to that, the group plans to create a holding company (Safmar Financial Investments) listing on the Moscow Stock Exchange combining 51% of the Europlan free float, 100% of NPF Safmar and 49% of VSK. It will have an initial market capitalisation of RUB15bn., reports IPE.